“Our ability to perceive quality in nature begins as in art with the pretty. It expands through successive stages of the beautiful to values as yet uncaptured by language. The quality of cranes lies, I think, in this higher gamut, as yet beyond the reach of words.” ~ Aldo Leopold, Marshland Elegy, A Sand County Almanac

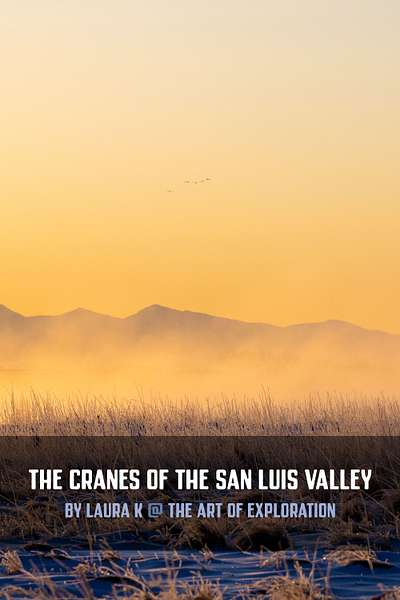

It’s early March, and I’m heading over La Veta Pass in the Sangre De Cristo Mountains towards Monte Vista, a small town in the San Luis Valley of south-central Colorado. The weather’s iffy and temperamental—typical for March. I keep my eye on a swirl of dark clouds up ahead. As the road climbs and bends, sleet whips across the windshield. The pavement is wet, though not yet slick. Snow covers the rising, rolling terrain ahead.

As mountain passes go, La Veta is relatively mild. But in March, I take nothing for granted and steer carefully, hoping the weather holds. The highway crests the ridge at 9,220 feet, and I relax as it winds down the western slope. The terrain opens to an expansive vista and the sun breaks through the clouds.

The road circles around the south shoulder of Blanca Peak. At its base lies a barley field gilded in evening sunlight. In the field, something catches my eye, and I realize that I’m seeing for the first time the very reason for my journey. There in the field, a group of about a dozen greater sandhill cranes stands with their long necks bowed to the ground, foraging leftover barley amongst the clipped stalks.

It’s been over a decade since I set out to witness a sandhill crane migration up close. I was living in northern Illinois when, on a whim, I attended a lecture about cranes, not knowing the fascinating world I was about to enter. I don’t recall every detail of the talk, but I do remember its effect on me. I was captivated by what I was told about cranes and alarmed to hear of their vulnerability. When I asked the lecturer what I could do to help, he told me to seek out the International Crane Foundation.

Founded in 1973 by ornithologists Ron Sauey and George Archibald, the International Crane Foundation (ICF) works to protect crane species around the world. Crane conservation is an extraordinarily complex undertaking. There are 15 species of cranes alive today, ten of which face a considerable risk of extinction. Although themselves hardy birds, cranes rely on fragile, declining ecosystems. To complicate matters, cranes are migratory, and their survival depends on conservation efforts that cross borders and connect cultures.

In the summer of 2010, not long after I attended the crane lecture, I visited the ICF headquarters in Baraboo, Wisconsin. The facility included over 250 acres of prairie habitats and sheltered a flock of 100 cranes. All 15 species of cranes were present at the facility, housed in large enclosures that brimmed with natural vegetation. But the facility was more than just a sanctuary. It was—and is—a place for advanced research in captive breeding and species reintroduction.

I explored the live crane exhibits and marveled at their beauty and variety. There were blue cranes from South Africa with long sooty wing feathers that draped behind them as they walked. There were hooded cranes, among the smallest of the crane species—though still demonstrably large birds—who winter in the boreal forests of Siberia and breed in the wetlands of China. There were red-crowned cranes, the largest of the world’s crane species, with body feathers so white they glowed like new snow. And there were others—whooping cranes, white-naped cranes, demoiselle cranes, sandhill cranes—all magnificent in their ways.

I took a guided tour and learned of the ICF’s tireless efforts to save the whooping crane—North America’s most endangered bird, whose population dwindled to fewer than 20 individuals in 1941. I discovered, too, that another North American crane, the sandhill crane, once threatened, was now on good footing in the wild. I decided then to try and see the sandhill cranes myself along one of their migratory routes.

Today, more than 800,000 sandhill cranes travel along multiple flyways across North America. Each spring and fall, the cranes gather to recharge at stopover points along their journey—places such as the marshy Sandhills of Nebraska and the wet meadows of Colorado’s San Luis Valley.

There are six subspecies of sandhills, distinguished roughly by their separate ranges. The greater sandhill crane, Antigone canadensis tabida, the subspecies I plan to see, winters in New Mexico, migrates through the San Luis Valley of Colorado, and breeds in Wyoming.

I’m groggy from the long drive, but the sandhill cranes I spot south of Blanca Peak revive me. I think of the time it’s taken me to get here—the many years I’ve tried to wrangle my schedule and budget to allow me this trip. Only now have I managed it. I arrive at my hotel after dark, unpack, eat a quick dinner and go to bed. It will be an early start tomorrow, and I don’t want to miss a moment.

The next day, I arrive at Monte Vista National Wildlife Refuge at dawn, hoping to spot the cranes in their roosting habitat before they fly over to the feeding grounds. When I enter the refuge, the road disappears into dense fog.

I drive slowly for two miles, then pull over and turn off the car. I roll down the window to listen. And there it is—a thick chatter of a greater sandhill crane flock roosting nearby. Their calm vocalizations consist of trills, peeps, and rattling purrs. The cranes use these soothing sounds to reinforce community and reassure each other that all is safe.

The sun climbs in the sky and begins to desiccate the brume. Gradually, I make out the contours of nearby trees. The cranes’ chatter crescendoes now. Slowly, the birds take flight, heading to the fields to forage. Some fly nearby, and although I don’t see them in the mist, I know they’re close when their trumpet calls crack the air around me.

The air finally clears, and the birds decamp in noisy gangs. They fly low and straight over the landscape to the fields on the western side of the refuge.

Each spring, the town of Monte Vista holds a festival to celebrate the stopover of the cranes. The festival is a mix of fundraising activities for crane conservation—an art show, nature exhibits, and vendor booths chock-full of bric-a-brac. I set aside a few hours one afternoon to explore the festival and am pleased to unearth a few science-minded events that interest me. I sign up for a bus tour of the wildlife refuge and the keynote presentation in the evening.

On the bus tour, a refuge naturalist tells us about the habits of cranes—how they shelter together each night in shallow water where predators dare not approach. During the day, they gather in meadows and fields to socialize and feed. We also learn that with cranes, the gravest concern isn’t climate change; it’s the destruction of their habitat.

The bus stops at a viewing area in the southwest corner of the reserve. There, the guides mount spotting scopes on tripods for us to observe the greater sandhills as they graze, trumpet, and perform courtship dances. When the sun sinks low over the mountains, the cranes take to the air and return to their roosting sites in the nearby wetlands.

That evening, I attend the keynote presentation. I’m thrilled to discover that the presenter is George Archibald, co-founder of the International Crane Foundation. Dr. Archibald’s talk reflects on the achievements of the ICF, now in its 50th year. In that time, the ICF has led numerous international, community-based conservation programs. It has preserved vast areas of critical crane habitat. And it has brought the whooping crane back from the brink of extinction, with wild individuals now numbering 800 individuals.

All are stunning achievements, but today’s volatile human-dominated world demands sustained conservation efforts. So that evening, I go online, make a donation, and renew my membership to the International Crane Foundation. It’s a small gesture when measured against the incredible achievements of conservationists like Dr. Archibald. But I am glad to be able to provide some support.

The time comes for me to head home, and I decide to take the mountainous route. The drive is both scenic and formidable, but I’ll arrive in time for dinner. The cranes will leave soon too. But their journey will be more daunting—and more spectacular—than mine.

When preparing to leave the valley, the cranes test the upper-level winds that will power their journey. They fly in a skyward spiral on thermals that lift them high enough to touch the heavenly winds. These powerful air currents can ferry the cranes 300 to 500 miles a day at impressive altitudes—as high as 13,000 feet over some mountain passes. But the cranes are cautious at first, and retreat to the ground if conditions are sketchy.

They’ll try again the next day. And the next.

When, at last, the cranes deem the winds reliable, instead of descending as they did on previous attempts, they plunge forward into the wild river of air. One after another, a precious thread of birds sets off, bound for their summer home.

If you enjoy The Art of Exploration, help keep the adventures rolling.

Leave some trail mix in the tip jar. Thanks!

Photographs

Photographs were taken by the author at Monte Vista National Wildlife Refuge in March, 2023.

Notes

Alamosa and Monte Vista National Wildlife Refuge Complex. Audubon. Retrieved March 18, 2023, from https://www.audubon.org/important-bird-areas/alamosa-and-monte-vista-national-wildlife-refuge-complex

Blue Crane. Smithsonian’s National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute. Retrieved March 18, 2023, from https://nationalzoo.si.edu/animals/blue-crane

Crane FAQs and Facts. Colorado Crane Conservation Coalition. Retrieved March 19, 2023, from https://coloradocranes.org/crane-faqs-and-facts/

History & Mission. The International Crane Foundation. Retrieved March 18, 2023, from https://savingcranes.org/about/history-mission/

Leopold, Aldo. A Sand County Almanac and Sketches Here and There. Oxford University Press, 1949.

Red-Crowned Crane. Smithsonian’s National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute. Retrieved March 18, 2023, from https://nationalzoo.si.edu/animals/red-crowned-crane

Sandhill Crane. The International Crane Foundation. Retrieved March 18, 2023, from https://savingcranes.org/learn/species-field-guide/sandhill-crane/

Sandhill Crane Antigone canadensis. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved March 19, 2023, from https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/sancra/cur/introduction

Species Field Guide. The International Crane Foundation. Retrieved March 18, 2023, from https://savingcranes.org/learn/species-field-guide/

Whooping Crane. Smithsonian’s National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute. Retrieved March 18, 2023, from https://nationalzoo.si.edu/animals/whooping-crane